Mazes and labyrinths can be confusing, frustrating, oppressive, nightmarish. They are the kinds of structures videogame developers are reluctant to put in their games, because the potential for the player losing heart or patience is relatively high. But as productions, they can be strangely economical, oddly light-footed. Mazes and labyrinths, after all, twist up space and as such, discover or create additional space within space. They allow vast journeys to happen within areas that are modest when judged in terms of square footage, journeys that encompass a multitude of locations that have an inherent, automatic atmosphere: tantalising forks in the path and mocking dead ends, hubs with corridors leading in all directions, leisurely perimeter paths and gristly knots of inner passages.

As such, I think they’re useful to reflect on at a time when the mantra of growth for its own sake has conquered the heart of videogame world design: bigger budgets for grander maps in terms of both explorable area and computational resource, all the way to Armageddon (did you know that Suicide Squad’s Metropolis is twice the size of Arkham Knight’s Gotham City?). But don’t take it from me, an armchair developer with armchair socialist sensibilities. Take it from The Legend of Zelda.

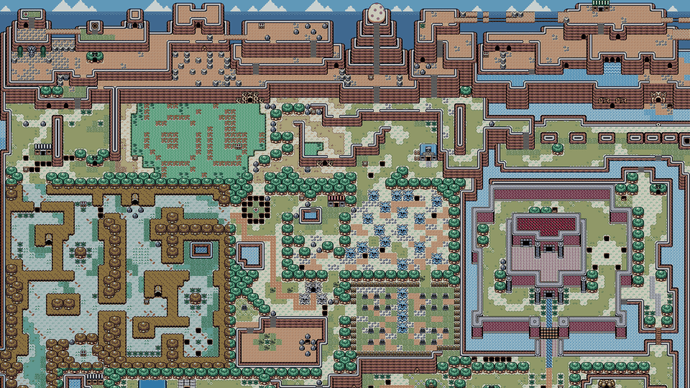

Zelda has a good track record for mazes and labyrinths – there’s the Lost Woods in Breath of the Wild, for example, a maze for the ears as much as the eyes – but it wasn’t until I read this essay from Zelda disassembly project LADX that I realised that the world map of dreamy, Twin Peaks-informed Link’s Awakening is one of its finest such spaces. As blogger Kemenaran explains, the Game Boy’s shortage of VRAM obliged Nintendo to be cunning when laying out the map, which is broken into clusters of “rooms” that share a specific graphics tileset. The game animates transitions between these rooms, which means that both rooms in question are visible at the same time. As such, each room’s tileset has to be available in VRAM simultaneously.

This would have been impossible to perform without glitches, if you could travel in any direction from any room, as in the latest open world games. After all, every adjacent room and its tileset would need to be loaded into VRAM at once. But as Kemenaran goes on, Link’s Awakening solves the problem by giving its map “a labyrinthine structure”, with routes screened off and winding around each other, so that you must always pass through certain “buffer” rooms that divide up the tilesets to fit the console’s capabilities, in place of a memory management system. Far from feeling like a deficiency, the essay goes on, these “folds also make the world feel larger, like a curated garden with carefully placed occluders.” It’s a lesson in how a world needn’t be big to seem huge.

That kind of back-and-forthy, “labyrinthine” design appears in many games. It doesn’t have to involve an actual labyrinth: what I’m trying to do with this post isn’t call for more mazes and labyrinths in games, but frame and advocate for a certain, secretive architectural sensibility, a mazy methodology that has persisted in spite of calls for worlds of ever-greater scale. I think the idea of a labyrinth or maze has much to offer conversations around sustainable game development, inasmuch as the premise is to unpack a given space, to deepen and enrich and mystify it, rather than simply add to it.

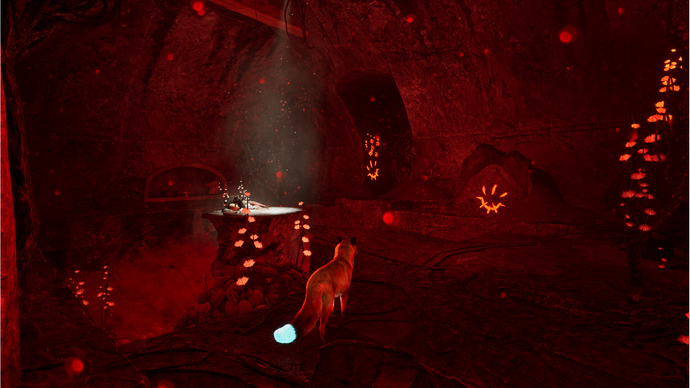

I recently played a game that’s currently under embargo, in which you travel around a stony, soggy wilderness consisting of ominous caves, lowering forests and fearful villages. The game in question has vastly more memory to draw upon than Link’s Awakening, but it’s subject to comparable production pressures. It’s the work of a mid-sized team who are trying to make something a little Assassin’s Creedy but with a fraction of the resources – and as such, it has a labour-saving touch of the labyrinth to it. Paths with invisible boundaries oscillate back towards each other in such a way that you can see where you were 10 minutes ago, and where you’ll be five minutes from now, even as the dripping rocks and foliage seem to press in relentlessly.

Going by what I was told on the day, this mazelike geography makes life a little easier for the developers, allowing for a feeling of vastness without quite as much toil. The world appears utterly open-ended when viewed from the map screen, but zoom in, and the coloured regions and nodes resolve into a series of branching paths. It’s another “curated garden with carefully placed occluders” – though unlike Link’s Awakening, it permits you to peer through the gaps – and again, this economical folding of the world is a positive for the player.

It makes this landscape intriguing, more substantial. The switchbacks lengthen the trek in a way that doesn’t just feel like “padding”: it’s less about artificially extending the playtime than inviting you to spend that time in a more appreciative way, to enjoy your surroundings properly. And there is something strangely restful about it that owes something to the present cultural moment. In the context of open world projects that sometimes seem as exhausting to play as they are to develop, whose very size transforms their painstakingly wrought fixtures into white noise and friction, it’s consoling to wander a world that feels built in such a way as to refocus the act of covering ground within it. The labyrinthine design makes me more mindful of the labour of that world’s creators, and more inclined to see them in the thing they’ve made.

Perhaps you could even call it therapeutic. While they’re associated in much literature with harrowing introspection and oversized monster encounters, labyrinths – in which there is only one path and thus, no possibility of getting lost – have enjoyed an unexpected career as a kind of mental health tool, linked to a variety of religious traditions. I’ve been to a couple of meditation workshops that feature labyrinth walking, wherein you amble slowly to the centre of a room-sized paper labyrinth and back out again. There’s no Minotaur to worry about, though I did fall over once while trying to let an old lady overtake.

The point of the experience, for me, is analogous to the sense of relief I get from games that are designed in a labyrinthine way. It allows me to re-obtain the space of the room and perceive other spaces within it, fresh contours and dimensions made available to me by magic. It’s a gentle concentration of my time that lends itself to a broader sense of possibility.