But you know. In a good way. My waking hours are, currently, beset by stress and anxiety from a number of different directions, and I’ve only had time to play about about an hour of Mediterranea Inferno so far. It’s quite a short game, though, and I’m sort of transfixed. It’s about three men in their early 20s who, pre-pandemic, were the toast of their party scene in Milan, and after a couple of years apart enforced by a lockdown they’re reuniting for a summer mini-break. Having blazed through my early 20s I no longer really remember that unique, potent mix of feeling simultaneously fragile and invincible, but it’s captured in this almost occult, yet hyper-real visual novel.

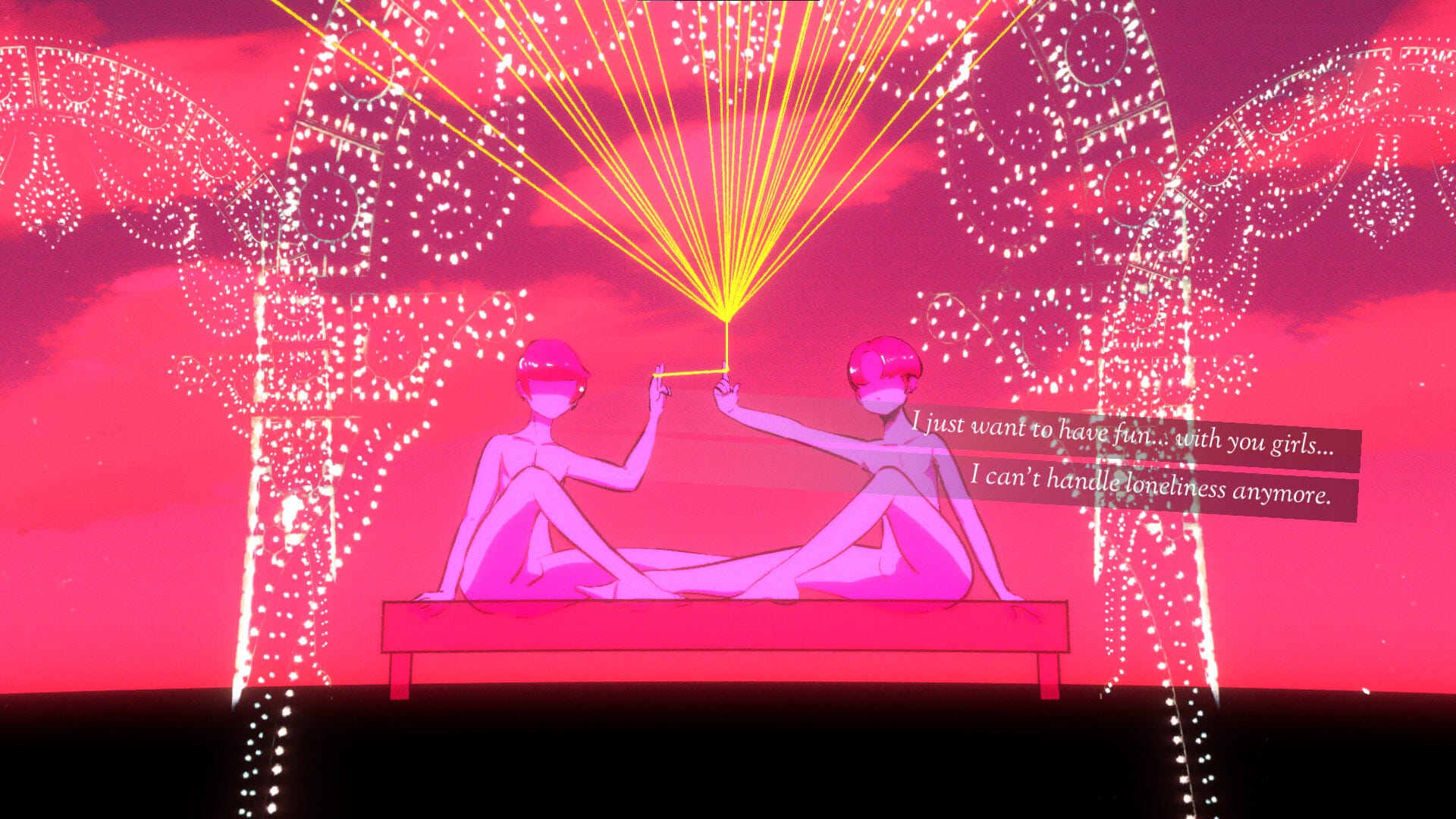

I may be playing on a Steam Deck on a rainy day, but the bold colour contrasts and the desperate enthusiasm of the dialogue really get over the feeling of a too-hot summer, of trying to force fun and recapture a friendship when you all want different things. The most intense segments of Mediterranea Inferno are the Mirages, visions that merge past and present and metaphor, giving explicit form to each character’s wants and anxieties. It’s unreal and yet a distillation of reality. It’s quite an intense ride so far, but it’s a good one.

It’s possible that I wouldn’t react so strongly to Mediterranea Inferno if I was’t having a bit of an angy time, but here we are. I’m not usually a big one for visual novels, but this one is extremely parsable to me. Mida, for example, is a successful fashion influencer who wants to prove that he’s independent – who is anxious about being emotionally vulnerable and thus views social media adoration as the only way to experience love without the risk of pain. Mida’s first Mirage – Mirages, by the way, are initiated by skinning and eating a mystical fruit offered by a temptation demon – takes place at the bottom of a pool, where, as the water becomes increasingly cholorinated and purified, Mida is seeing his friends through the shifting ripples of the water. He sees circling sharks, and then fans taking pictures as if Mida himself is a specimen in an aquarium. In another Mirage, Mida is stitched to his friends by myriad electric sewing machines, but snips the golden threads binding them.

Claudio, who initiated the holiday, is trying to figure out who he wants to be, and feels the pressure of living up to his grandfather’s example – a successful, respected man. His first Mirage emphasises the feeling of being watched and judged with obvious religious imagery. He gives confession to a giant eye, and sees a shrine to Mary Magdalene, which becomes surrounded by dozens of images of her. The statue on the shrine becomes an image of him, and merges into saints and deities from other religions, too.

But it’s tense. Everyone is on edge. The game’s intensity of colour is almost headache-inducing even as it’s beautiful, nailing the characters and imagery to the back of your eyeballs. It’s not subtle, but it’s not meant to be, and it’s extremely effective as a result. It’s weird and a bit sinister, hallucinatory and dark, and you get the feeling it’s only a few degrees away from a slasher movie. To the extent that I’m not a big visual novel gal, you might call it a visual novel for people who don’t like visual novels – except it’s not embarassed about what it is at all. I haven’t played Milky Way Prince – The Vampire Star, the previous game from the same creator, but now I want to.

I’m chummy with Pietro Righi Riva, publisher Santa Ragione’s studio director, to the extend that we talk about horror stuff and I make fun of him for watching Star Wars TV shows.